When I was in law school from 1982 to 1985, I interviewed for summer jobs with a number of firms in Boston and New York.

I recall the partners who met with me, almost invariably white men (in those days, each firm typically had two women: one in trusts and estates, and another intrepid pioneer in litigation or corporate). These men were, by and large, happy with their lives.

Author Anne-Marie Slaughter, here addressing

the LCLD 2013 Annual Membership Meeting.

They were generalists, men who thrived on the varied pace and substance of different cases or deals. They were respected counselors to their clients. They knew their fellow partners, and understood what it was to be part of a partnership rather than a corporate hierarchy. They also had lives outside the law, as writers, civic leaders, fathers and weekend golfers. They worked hard and reaped the rewards, both intellectual and material, of a prosperous profession. They could, and did, urge law students like me to follow in their footsteps.

Fast forward ten or fifteen years, to a time when I was a law professor and, later, a professor of politics and international affairs.

When undergraduates interested in foreign policy came to me for career advice, I often advised them to go to law school. It is a spectacular training for the mind, I told them, reflecting on how my own law school experience had sharpened my analytical and writing skills. They should also practice law for awhile. That way they could pay off their law school debt, as I had, while acquiring practical experience and credentials so that law would always remain a satisfying fall-back profession.

To build a happier, healthier, and more attractive legal profession, diversify your work force—and your ways of working.

Today I know relatively few happy lawyers, whether associates or partners, and I no longer advise students to pursue law as a path to a career in foreign policy. I still believe in the value of a legal education, but it is far more expensive and far less likely to lead to a rewarding job than it was thirty years ago.

Law has become a brutal business, demanding longer and longer hours and a continuous hunt for clients, even among partners. The once-cherished notion that partners are equals, meriting equal pay and respect, has gone the way of the VCR. Today, time for parenting, much less civic engagement or writing essays or even novels on the side, is nearly impossible to come by. Even golfers are hurrying through their rounds. No wonder young people are having second thoughts about law as a career.

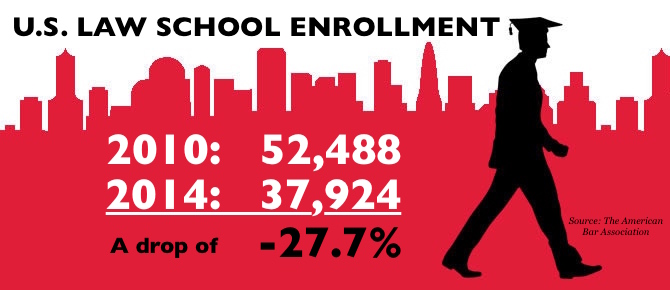

This is not news. In 2014 the ABA reported that the numbers of first-year law students were the lowest in 41 years, since 1973. And in March 2015 the organization that administers the LSAT announced that law school applications were on track to be 50 percent lower than in 2004. Emory tax law professor Dorothy Brown wrote in The Washington Post that “law schools are in a death spiral.”

Law firms are also hemorrhaging talent, particularly female talent once childbearing kicks in. Every time an associate leaves or is derailed from the leadership track — torn between billing 2,000 hours a year and caring for children or elderly parents, or simply having a life — the firm loses all the time and energy it spent recruiting and training her or him. It must then invest even more time and money finding a replacement who may not be as good.

The cure is diversity. That assertion may not come as a surprise to Members of the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity, who are personally committed to fostering diversity of gender, ethnicity, race, and sexual orientation in the profession. But I’m also talking about diversity in ways of working. Both kinds of diversity are essential to reinventing law practice. And the two are interrelated.

The proposition is simple. Different people, from different backgrounds and with different life experiences, who have not been schooled in the traditional ways of legal practice through their fathers, uncles, and brothers, are far freer to reimagine what could be.

Is it accidental that one of our most prominent re-imaginers — Deborah Epstein Henry, author of Law and ReOrder and the new Finding Bliss, which describes many new legal models — is a woman? Or that a New York Times story on The Geller Group described a six-woman firm without an actual office determined to “show that parents can nurture their professional ambitions while being fully present in their children’s lives”?

It’s not just women who are pushing for change. Male attorneys from diverse backgrounds, whose families do not include long lines of lawyers, can look at the hallowed traditions of white shoe firms and ask “why?” Why do we have to work this way? Why isn’t it possible to practice law and also live a rich and rewarding life?

Those traditions, it turns out, are not so hallowed after all.

I was surprised to learn that the practice of “billable hours” is actually a relatively recent phenomenon. A senior partner in a big New York firm explained to me that until the 1970s, most firms billed fee for service, on the assumption that law was a gentleman’s profession. Gentlemen would fairly and honestly assess what a particular service was worth, bill it, and their equally gentlemanly clients would pay it. Isn’t it time to restore this system, or something like it? What was done can be undone!

Equally important, when I was in law school our heroes were the public interest lawyers who had litigated Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainright, and Roe v. Wade. We saw lawyers as warriors for justice. Today that vision still glimmers when we look to lawyers like Robbie Kaplan, who argued United States v. Windsor. Yet the courts have become far less hospitable to public interest litigation; we have also learned that clients and their lawyers define the “public interest” very differently.

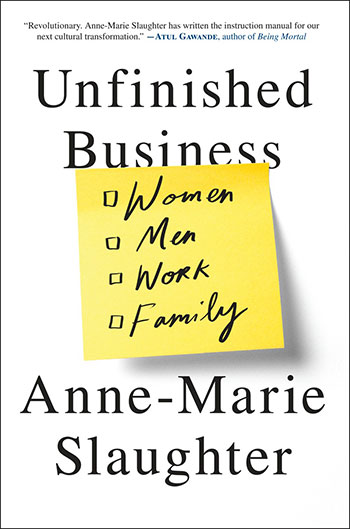

I propose that we reimagine law less as a fighting profession than as a caring one. The central argument of my new book, Unfinished Business: Women, Men, Work, Family, is that to achieve genuine equality between women and men we not only need to advance women in specific positions, but we must also elevate the value of what was traditionally women’s work — caring for others. Medicine is typically defined as a caring profession, but law can and should be as well.

Lawyers who come from different communities and walks of life are more likely to have seen different faces of the law, serving as well as punishing. They may be more open to the virtues and profits from small law, even as Big Law is in decline. In a rule-of-law society, law provides the rules and tools to help people who need to make a living, work in safe spaces, get an education for themselves and their families, secure housing, enforce contracts, preserve their physical security, obtain medical benefits, and pass on their worldly goods to their families.

In short, the solution to the current crisis in the legal profession is indeed diversity, but diversity in ways of working as much as among the workers themselves. Ways of working that leave room for lives outside the law will improve the productivity and quality of legal practice.

They will also create happier, healthier, and richer lawyers, in all the ways that matter.

Anne-Marie Slaughter is the author of Unfinished Business: Women, Men, Work, Family, one of seven books to her credit over the past decade. After a distinguished legal career that included a professorship at Harvard Law School, she served as Director of Policy Planning at the U.S. State Department and as Dean of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. She is president and CEO of New America, where she writes often about U.S. foreign policy. She is also an advocate for American families in a fast-changing world. To see her presentation to the 2013 LCLD Annual Membership Meeting, click here.