African American communities celebrated Emancipation Day, or Juneteenth, with music, flags, and barbecues. (Photo courtesy Texas Monthly)

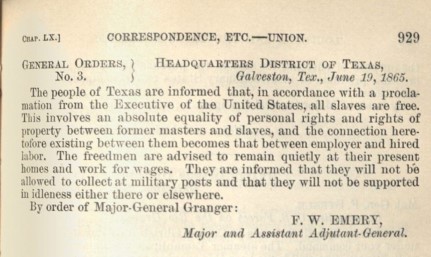

On June 19, 1865, about two months after the surrender of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, Va., U.S. Army Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, to read General Order Number 3 of the U.S. Congress (below), informing enslaved African Americans of their freedom and that the Civil War had ended.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, ‘all slaves are free,’ ” the order reads.

General Granger’s announcement put into effect the Emancipation Proclamation, which had been issued more than two years earlier, on Jan. 1, 1863, by President Abraham Lincoln.

Large celebrations on June 19 began in 1866 and continued regularly into the early 20th century. The holiday became known in Texas as Juneteenth when celebrants combined the words "June" and "nineteenth." The day is also sometimes called “Juneteenth Independence Day,” “Freedom Day,” or “Emancipation Day.”

African Americans treated this day like the Fourth of July, and the celebrations were similar. In the early days, Juneteenth celebrations often included a prayer service, speakers with inspirational messages, reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, stories from former slaves, food, games, rodeos, and dances.

The celebration of June 19 as Emancipation Day spread from Texas to the neighboring states of Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. It also appeared in Alabama, Florida, and California as African-American Texans migrated to other parts of the country.

Today, amid sustained calls for racial justice in America, the holiday has new relevance, including a groundswell of support for declaring Juneteenth a national holiday.